It seems simple—just tell families to eat less sugar. But added sugar is everywhere, sometimes in foods we think are healthy. These “sneaky sugars” are lurking in foods where we’d never suspect it.

Most families would be surprised to learn that their children are each consuming 18 teaspoons a day, or three times the daily recommended limit for added sugar. Too much added sugar can lead to weight gain and health problems such as diabetes and high blood pressure.

One mom and pediatrician is on a mission to make it easier for families to make healthier choices.

Anisha Patel, MD, MSPH, Arline and Pete Harman Endowed Faculty Scholar, and her team of Stanford researchers started by working with Bay Area schools to install lead-free water bottle filling stations at schools, so that children would have an appealing source of fresh water and drink less juice and soda.

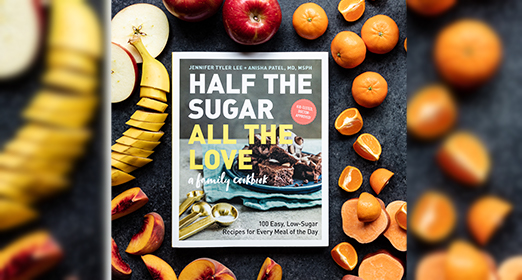

More recently, Patel co-authored a cookbook titled Half the Sugar, All the Love. The book shows families how to prepare low-sugar versions of their favorite foods at home together. The recipes are simple to make and cover a wide range of cuisines, including instant oatmeal, pad thai, horchata, spaghetti and meatballs, Korean chicken wings, and chai-spiced rice pudding.

Sample Dr. Patel’s banana bread recipe.

We spoke with Patel about ways that families can reduce added sugar while still enjoying the foods they love. Shelter-in-place orders due to COVID-19 brought a resurgence in home-cooked family meals, and Patel offers many practical tips for families to shop for and prepare healthy and delicious food.

Q: What would parents be surprised to learn about sugar?

PATEL: While most parents know that cakes, cookies, candies, and sugary drinks are high in added sugar, they are surprised to learn that added sugar sneaks into seemingly healthy foods like soups, salad dressings, sauces, cereals, granolas, nut butters, and yogurt.

Added sugars are those sugars that are added to foods and beverages during cooking or before serving. Added sugars include refined sugars, such as granulated sugar, and unrefined sugars, such as honey. They do not include naturally occurring sugars in fruits, vegetables, and dairy. These sugars are different, because they are accompanied by fiber and other nutrients.

Q: How can families eat less added sugar?

One clever strategy is to use naturally sweet, fiber-rich fruits and vegetables in place of sugar to add flavor to your favorite foods. Many of the recipes in the cookbook use dates or fresh fruit or vegetables to add sweetness.

Q: What do you do in your own home?

We try to eat most of our meals at home. Eating at home doesn’t mean you have to cook everything from scratch. Due to our hectic schedules, we often combine healthier, lower-sugar packaged foods with fresh items to cut down on the meal prep and cooking times. Once a week, we go out to a family meal at a local restaurant.

Q: Does your family have a favorite recipe from Half the Sugar, All the Love?

My daughters, ages 8 and 13, have tested every recipe in the book. Our favorites are the Chinese Chicken Lettuce Cups and the Poke Bowls, because each person can customize his or her own toppings. We usually use brown rice instead of white rice. If you are trying to cut down on carbohydrates, you can also omit the rice or use riced cauliflower.

Q: What inspires your research?

My research is focused on reducing disparities in chronic diseases among low-income populations. This interest stems from my upbringing in North Carolina. With a median household income of around $33,000 and a poverty rate of 28 percent, my hometown has a life expectancy 10 years lower than cities in Santa Clara County. The disparities in income, education, and health are growing across the country, and they continue to shape my research interests.

Q: When did you become concerned about sugar?

As a Stanford pediatrics resident nearly two decades ago, I saw many children from low-income communities in my clinic who were overweight and had related conditions. When I counseled families to eat more fruits and vegetables or to be more active, they told me that they had no grocery store in their community and did not feel safe being outside. This ignited my interest in collaborating with communities to ensure that the healthy choice was an easier choice.

Q: Why is philanthropy important to your work?

I have been fortunate to receive a faculty scholar award from the donor-supported Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute. This award has supported my research and career development and has allowed me to collaborate with investigators outside of the School of Medicine.

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2020 issue of Packard Children’s News.