It’s fitting that the top floor of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford offers cures that seemed pie in the sky only a few years ago.

The new fifth floor, which is opening in the winter, is a wondrous place, bustling with bright minds that meld research and first-class patient care to redefine what’s possible in medicine and—most importantly—to save children’s lives.

The fifth floor is where seriously ill children come for care and where groundbreaking advances are made. To put it simply, it’s where families come for hope. Often, they’ve tried every established therapy available and have gone through the pain and stress of hearing nothing was working. They need a medical breakthrough, and that’s exactly what the fifth floor offers.

Take 15-year-old Peter Hanson, for instance. This smart, active teen has had his fair share of serious health challenges, but he’s beaten all of them—even the rare ones—thanks to Packard Children’s. At age 2, Peter had a heart transplant followed by chronic ear infections, a broken leg, repeated bouts of pneumonia, and bewildering ciliary dyskinesia, a condition where cilia cells in the lungs don’t work properly.

Then at age 8, he developed angioimmuno-blastic T-cell lymphoma, a little-known cancer never before seen in a child.

“It was so rare, there was literally no data on it. We feel lucky to live near world-class doctors who could handle Peter’s complicated medical issues,” says Katharine Hanson, Peter’s mom.

Transplant Defies the Odds

Standard cancer treatments were not working on Peter’s lymphoma, so he was referred to Kenneth Weinberg, MD, Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor in Pediatric Blood Diseases. As Peter’s case was incredibly complex, Weinberg thought Alice Bertaina, MD, PhD, who is developing a revolutionary strategy to create compatible donor stem cells for patients who don’t have a strong enough match, could help. Bertaina is improving upon a form of stem cell transplants, called haplo-identical stem cell transplants. They’re special because they let doctors use cells from a partially matching relative. For Peter, it was his mother.

“The minute we met Dr. Bertaina, we put our confidence in her—she’s so smart and incredibly nice. That overlap can be rare, but we’ve found it in many Packard Children’s doctors,” Katharine says. “My husband, Charles, and I basically flipped a coin to see who would be a donor. Being a donor really wasn’t that difficult.”

Children may have to wait a long time for a donor match, sometimes running out of time. Haplo-identical transplants expand the number of children who can receive life-saving transplants.

In early studies, Bertaina safely cured 90 percent of children with nonmalignant diseases and nearly 70 percent of children with leukemia. She has performed transplants on over 400 patients using this technique in clinical trials. Next, she hopes to modify the process to further reduce the risk of graft-versus-host disease—a condition where donor cells attack a patient’s cells. She’s also taking what she calls a sophisticated approach to reducing the risk of infections and leukemia relapse after transplantation.

Peter’s stem cell transplant was extra challenging for Bertaina because he was one of only a few people in the world with a transplanted heart to receive a stem cell transplant. She ran the risk of Peter’s heart rejecting his new stem cells and failing. That’s why they first tried an autologous transplant using Peter’s own blood-forming stem cells. It seemed to work for a year, and then it failed. They had only one more option—the haplo-identical stem cell transplant. To lessen the risk that his heart would reject it, Bertaina removed T-cells from Katharine’s donor blood—standard for haplo-identical transplants—and then worked with a pharmaceutical company to develop a special drug to essentially turn off the transplant if things went wrong. Luckily, they didn’t.

“The stem cell transplant was by far the best treatment he received. It allowed him to feel well most of the time and be a regular kid,” Katharine says.

Today—two years later—Peter is a typical sophomore in high school who enjoys playing video games with friends, practicing driving in parking lots, excelling at school, and thinking about his future. This past summer he attended an EXPLO Medical Rounds camp at Wellesley College, which strengthened his interest in medicine as a career. He attends Menlo School in Atherton, where his parents are history teachers.

For Peter, the highlight of the stem cell transplant is that he doesn’t have to go to the hospital regularly anymore, even though he’s grateful for the incredible care he received.

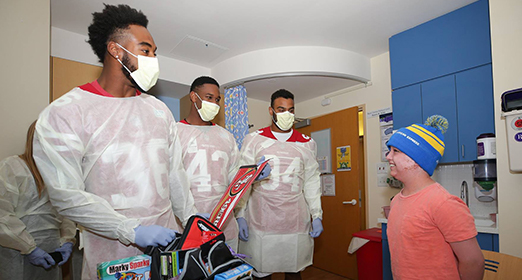

“The best part of my transplant hospitalization was when I was visited by my friends—and by players from the San Francisco 49ers,” says Peter.

The new fifth floor gives Bertaina and others space to increase the number of stem cell transplants performed—saving even more children like Peter.

A Life Free of Transfusions

Meet 4-year-old Miya Nguyen, a vivacious little girl born with alpha thalassemia, a rare genetic blood disorder that often results in miscarriage. Her parents, Cindy and Tony, already had two sons, but they really wanted a third child. They’d tried for years to conceive, with two pregnancies failing due to alpha thalassemia. Then, after giving up, Cindy got pregnant with Miya.

Cindy works as a patient service representative at Palo Alto Medical Foundation (PAMF), and Tony is a deep-sea fisherman. During her pregnancy, Cindy saw a maternal-fetal medicine specialist with PAMF who ran tests and confirmed that Miya also had alpha thalassemia, but at the same time told Cindy about cutting-edge intrauterine blood transfusions that could help the baby reach full term. Cindy had several transfusions and delivered Miya at 32 weeks.

Shortly after birth, Miya was transferred to Packard Children’s neonatal intensive care unit for lung support, and she stayed for a month. After discharge, Miya returned regularly to get blood transfusions for her alpha thalassemia. The best treatment for most thalassemias is a bone marrow transplant—a type of stem cell transplant in which donor blood cells are harvested from bone marrow rather than from blood. To receive the transplant, Miya needed to first grow stronger. That time came when she was 9 months old. Luckily, Miya’s oldest brother, Anthony, was a full donor match.

In preparation for the transplant, Miya received chemotherapy to make room in her bone marrow for the new cells and to suppress her immune system to prevent rejection. Following the transplant, she stayed at Packard Children’s for several months to manage her post-transplant complications.

“We were so relieved that the bone marrow transplant was successful. Today, Miya is off all medications, and we only go back once a year for a checkup to make sure she hasn’t relapsed. So far, there are no signs of the alpha thalassemia,” says Cindy. “I am so thankful for everyone at Packard Children’s who helped us. It’s the only place we could get that kind of care.”

She describes Miya as a cheerful, playful girly-girl who loves to wear pink, sing, and dance. She has a little tomboy in her though—probably from her father—because she also loves to fish.

“She caught a fish on her first try. Maybe that’s why she likes it so much,” Cindy says. “That, and I got her a little princess fishing pole.”

In addition to alpha thalassemia, stem cell transplants are being used to treat other rare genetic diseases, including IPEX syndrome, severe combined immunodeficiency—made famous by the “bubble boy” story—and a life-threatening multisystem disorder called Schimke immuno-osseous dysplasia, among others. There is potential to apply this treatment to many more diseases.

The Fifth Floor Redefines Revolutionary Care

The new fifth floor is a space dedicated to discovery. The 65,000-square-foot floor has 49 beds and empowers Packard Children’s to treat almost twice as many children with cancer and blood and genetic diseases each year. One half—in the south tower—offers innovative research and pioneering therapies to children receiving stem cell transplants and gene therapies, often in clinical trials with the Center for Definitive and Curative Medicine.

The north tower’s fifth floor houses the innovative Bass Center for Childhood Cancer and Blood Diseases, which uses decades of experience and the newest science to treat children with cancer and blood diseases like sickle cell, hemophilia, and more. Several clinical trials using the latest cancer therapies are taking place now, with many more in the pipeline.

One of the most promising treatments already in use on the fifth floor for certain types of cancer is immunotherapy. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy is a type of immunotherapy that uses the body’s own immune system to fight cancer, reducing the need for chemotherapy and radiation.

Donors Are Making Cures Possible

The life-saving research and compassionate care taking place on the fifth floor and throughout Packard Children’s would not be possible without the community’s generous support. You have helped create this amazing place.

When the hospital was first designed, the fifth floor was a shelled space set aside for a future, somewhat nebulous need. But that need came quickly into focus as unprecedented discoveries in stem cell transplantation, cancer immunotherapy, gene therapy, and clinical trials showed us the future of pediatric medicine.

Donors have rallied behind this incredible work, making what once felt impossible possible. Among the gifts is a significant donation from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation to build out the fifth floor. Many others have believed in the power and potential of this work, including longtime supporters Anne and Robert Bass.

The fifth floor is the place where world-renowned experts gather to bring unique research and state-of-the-art care to give children like Peter and Miya the best chance at healthy childhoods.

The sky’s the limit for the possibilities it holds.

See how we’re making the impossible possible at supportLPCH.org/5thFloor.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of Packard Children's News.