How one family’s tragedy advanced newborn care worldwide.

Christopher Hess lived only a short while, but he has saved countless lives. That’s because Christopher’s legacy inspired a philanthropic commitment spanning more than four decades—one that has moved the needle on prematurity and transformed the future for newborns.

In January 1973, Robert “Rob” and Rosemarie Hess were excited to become parents to twins. But when Rosemarie gave birth weeks early, their baby girl, Verena, thrived, while Christopher succumbed to complications of extreme prematurity.

It’s a fate that claims too many infants: Premature birth is the leading cause of death in children under age 5 worldwide.

Rob and Rosemarie channeled their grief into purpose and began supporting prematurity research at Stanford, in the hope that other parents could avoid what they endured.

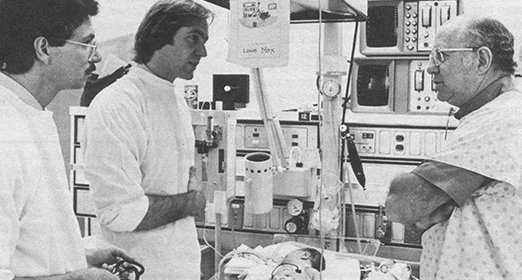

Their initial support was modest but meaningful, recalls Philip Sunshine, MD, the twins’ doctor. In addition to caring for at-risk newborns, Sunshine ran the Premature Infant Research Center, founded in 1962 and the earliest foray into prematurity research at Stanford Medicine.

Sunshine remembers receiving a heartfelt letter from the couple; he was surprised to find it included a $100 donation to his research. “I started to cry,” he says. “I couldn’t believe they were so generous.”

Their annual donations continued. Physician-researchers in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) were so touched by their giving that they invited the couple for a tour to see their gifts in action. That team included David Stevenson, MD, who would go on to launch Stanford’s Prematurity Research Center and is now senior associate dean for Maternal & Child Health.

“Rob saw in David [Stevenson] the future of neonatology,” Sunshine says. “Rob and David quickly formed a close bond. It was that bond that has been a key ingredient in their continued commitment to our neonatal program.”

A growing dedication

Over the years, the Hess family continued to give generously, as Rob advanced in his career at Raychem, a radiation chemistry company that makes heating and connectivity products. Rob went on to found companies that developed medical devices for interventional cardiology, giving him a nuanced understanding of health care.

“Rob always asks good, probing questions—some have even sparked research we have undertaken,” Stevenson says. “You can see his mind spinning on a topic. It sometimes seems like he could be a retired neonatologist.”

In 1993, the couple established the Christopher Hess Research Fund at the Stanford University School of Medicine. Rob and Rosemarie Hess earned the title of Stanford Associates—an honorary organization of Stanford University volunteers—before Rosemarie passed away in 2009.

When Rob later married pharmaceuticals professional Wendy Tomlin, she shared his philanthropic commitment. In the last decade, Rob and Wendy have established three key professorships in neonatal and developmental medicine, pediatrics, and clinical care, helping Stanford become a leader in the transdisciplinary approach that’s needed to tackle prematurity.

Pioneering innovations to save lives

One of the biggest recent innovations by the Stanford research team, made possible by philanthropy, is a simple blood test to predict preterm labor months in advance. The technology can also be used to predict preeclampsia, a hypertensive disorder that triggers preterm birth and can be dangerous and even fatal for pregnant women.

Another significant discovery was the connection between increased inflammation and preterm birth. Clinical trials have now demonstrated that a daily dose of aspirin can lower inflammation during pregnancy, thereby decreasing the risk of preterm labor and preeclampsia.

These groundbreaking solutions to a complex problem could change outcomes for women and babies across the globe, and they are just a few of the advances sparked by philanthropic support.

“We couldn’t have made these advances without the Hess family’s support over these past 45-plus years,” Stevenson says. “Their contributions set in motion a sea change in neonatal care. Many of the research breakthroughs that occurred here are now commonplace in NICUs across the country, thanks to their generosity.”

A new landscape

Today, the landscape looks a lot different from when the Hess family lost Christopher. Fifty years ago, a baby born at less than 28 weeks gestational age had a 10 percent chance of survival. It’s now close to 80 percent.

“The progress has been enormous,” says Wendy Tomlin-Hess. “We understood neonatal advances would not happen without the financing of research grants. It was very important for us as a family to continue moving this effort forward.”

The Hess family’s over four decades of philanthropy for maternal and child health at Stanford Medicine has advanced research to a point nobody could have imagined. Their substantial donations empowered Stanford Medicine to create one of the most prestigious and impactful neonatology and fetal medicine centers in the nation. What once was deemed impossible—ending premature births—now seems within reach.

Ten years ago, March of Dimes invested $20 million in seed funding to launch the Stanford Prematurity Research Center. The powerful one-two punch of support from March of Dimes along with the Hess family’s donations gave rise to astounding breakthroughs in predicting and preventing premature births and in caring for premature infants.

Nevertheless, there remains much to be discovered, tested, and implemented around the world. Progress hinges on philanthropy, and the potential is limitless.

“What better investment is there than helping babies?” says Sunshine. “You are investing in a person just starting out in the world rather than in someone at the end of their lifetime.”

Sadly, baby Christopher was new to this world and only here for a brief time, but the legacy of his short life lives on and the impact has been immeasurable.

“From their loss, the Hess family changed the future for so many,” Stevenson says. “For more than four decades, babies have benefited from their generosity, and that’s just the start. Countless more, here and across the globe, will benefit in the future.”

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2021 issue of Packard Children’s News.