The new Office of Child Health Equity gives children more opportunities for better health—and better lives.

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, it quickly became clear that some members of our community were bearing the brunt of the impact. Children and families faced a variety of challenges such as homelessness and food insecurity, which carried economic, emotional, and even health repercussions.

“COVID has shown us how people’s experiences, depending on where and how they live, generate different health outcomes,” says Lisa Chamberlain, MD, MPH, professor of pediatrics. “When we talk about these health inequities, we’re talking about differences that are, at their root, unjust and quite fixable, whether it’s access to health care, clean water, or healthy foods.”

In response, Chamberlain and her colleagues in the Department of Pediatrics in the Stanford University School of Medicine developed a new initiative: the Office of Child Health Equity. Launched in November 2021, the office advances the work started by the Pediatric Advocacy Program, a joint effort of the School of Medicine and Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, that Chamberlain and Janine Bruce, DrPH, founded more than 20 years ago. The new office will build on the program’s work by offering new strategies to address the factors that contribute to health inequities.

With the pandemic surging, the Office of Child Health Equity consulted with its network of community partners to determine where it could do the most good.

“It really emerged that children weren’t faring well,” says Bruce, who serves as associate director of the new office. “To care for the whole child, you have to look at the health of the whole family, and one of the first things we heard was that families didn’t have enough food.”

Delivering a Swift Response

To meet that need, the office coordinated the purchase and delivery of 32,000 pounds of much needed food, as well as the distribution of 500,000 diapers—an essential item that can prove

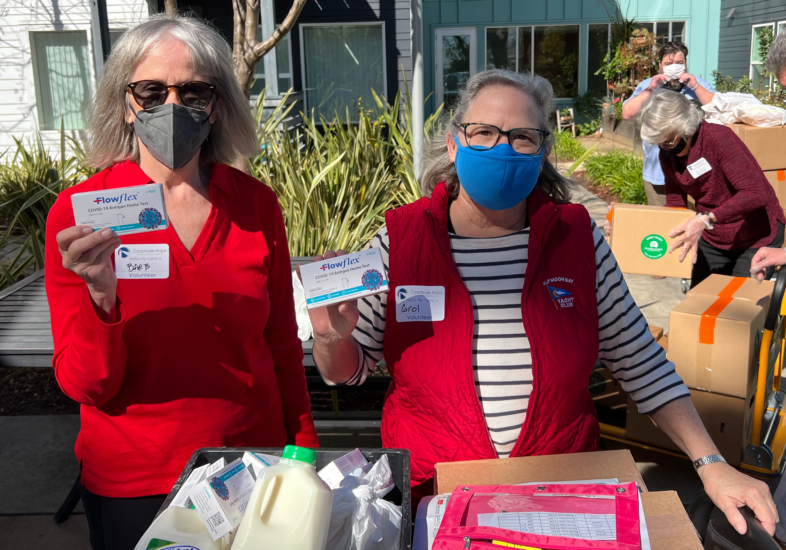

costly for low-income families. In addition, it distributed backpacks filled with school supplies, face masks, and COVID-19 antigen tests at community sites. “We sent 1,900 tests alone to the Ravenswood City School District, enough for almost every child and staff member,” says Bruce.

“I’m so appreciative of the generous philanthropic community that exists here,” Chamberlain adds. “It felt great to be able to support our neighbors when literally they were telling us they could no longer afford diapers, that their child was wearing the last diaper they had. So, we set up diaper pop-ups. We did all sorts of things to help us get everyone through.”

Chamberlain and her team were able to mobilize quickly during the pandemic thanks to donor support and the strong community relationships they have cultivated with organizations such as the Ravenswood City School District, Samaritan House in San Mateo, Second Harvest of Silicon Valley, and Help a Mother Out.

“The Office of Child Health Equity provides great thought partnership in how we can address childhood hunger and how we can collaborate to ensure that families have the support they need to raise happy, healthy, thriving children,” says Tracy Weatherby, vice president of strategy and advocacy, Second Harvest of Silicon Valley, a food bank that serves more than 450,000 people every month.

Vision for Large-Scale Change

While the Office of Child Health Equity’s efforts during the height of the pandemic were focused on the local community, the impact of its work will be felt around the state and nation—mostly by way of research. The office plans to take its own as well as other Stanford research findings on child health inequities and translate them into better health policy.

“This is the type of work we want to continue to do, to expand on the model we’ve developed,” explains Bruce. “We want to continue to be responsive to the community as an office at-large. And we want to conduct equity research and be part of the research work that translates from community service to policy many times over.”