This week, an extraordinary breakthrough at the Stanford School of Medicine brings hope to children and families facing devastating brain or spinal cord cancers typically considered incurable. The new study, published in Nature, demonstrates exciting promise for an immune-cell therapy in treating childhood tumors for which no effective therapy currently exists.

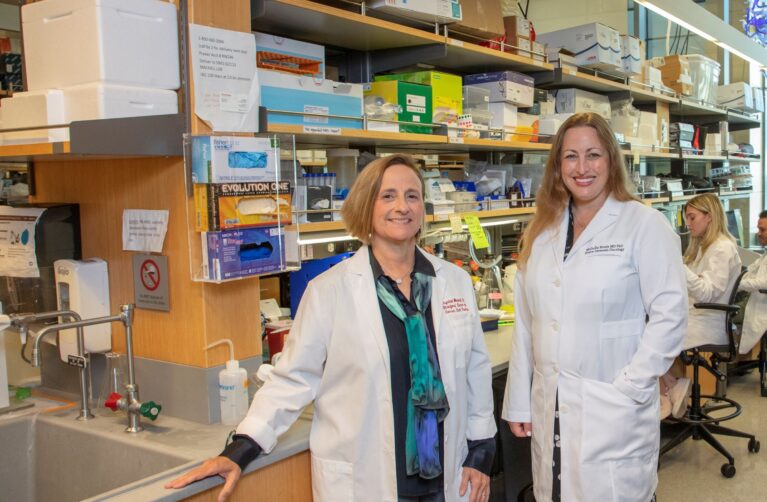

An astounding level of support from a passionate donor base fueled this game-changing discovery. Donations of all sizes, alongside tissue donations from grieving families, propelled the research. Michelle Monje, MD, PhD, the Milan Gambhir Professor of Pediatric Neuro-Oncology and lead author of the study, says, “These results—which make me more hopeful about a cure than I have ever been—owe so much to philanthropy and the families and foundations that have put their faith in our research.”

The study explores the use of CAR T-cell therapy to treat deadly cancers of the brain or spinal cord occurring most commonly in children—including diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), which impacts the brainstem. Not only is the clinical trial one of the first to demonstrate CAR T-cell efficacy against any solid tumor, the results are more encouraging than even the researchers had dared imagine. “One of the biggest surprises was how much clinical benefit we saw,” said the study’s senior author, Crystal Mackall, MD, the Ernest and Amelia Gallo Family Professor and professor of pediatrics and of medicine.

The therapy used in the clinical trial also recently received an FDA designation of regenerative medicine advanced therapy, or RMAT—available only to a small group of therapies with immense potential to treat life-threatening conditions. This designation is a major milestone, signaling that the agency will work closely with researchers to fast-track the path to FDA approval.

A Bleak Disease—and a Ray of Hope

A diagnosis of DIPG is exceptionally grim: The median survival time following a diagnosis is less than one year, and the five-year survival rate is below 1%. Existing chemotherapy drugs are useless against the tumors, radiation offers only temporary relief, and the tumors are inoperable because malignant cells are enmeshed with healthy cells in the brain and spinal cord.

The disease can result in profound disability as the fast-growing tumors progress. Among other effects, patients may lose their ability to walk, smile, swallow, hear, and talk. They might also experience neuropathic pain resulting from spinal cord damage, as well as paralysis, loss of sensation, and incontinence.

It’s against this dire backdrop that the results of the new Stanford study arrive. In a clinical trial with 11 participants receiving the therapy, nine patients showed clinical and/or imaging benefits, as well as improvement in disabilities. Additionally, in four participants, the volume of tumors decreased by more than half. And one trial participant, Drew, had a complete response: His tumor disappeared entirely from brain scans. He’s healthy now, four years after his diagnosis. The magnitude of this result—for a cancer that has until now been universally fatal—is hard to overstate.

An Outpouring of Donor Support

Over the last decade, donor support has catalyzed Monje’s research. New research ideas typically do not qualify for federal funding, and in the early stages of her investigations, philanthropy was essential to getting the research off the ground. Now, the rapid pace of Monje’s continuing discoveries—urgently awaited by desperate families—continues to owe much to passionate donor support.

In fact, few areas of pediatric research have ever received the type of overwhelming support that has fueled the progress in Monje’s lab over the last 14 years. The cumulative dollar amount of philanthropic support for her research—more than $25 million—is tremendous. Equally staggering is the fact that Monje has received gifts at all levels, ranging from $5 to $5 million, from a vast donor base comprising more than 1,000 individuals and foundations.

Bring Hope to Kids with Brain Tumors

Join us on this extraordinary journey. Make a contribution to drive life-saving research in the Monje lab.

The story of one early donor, Maiy’s Miracle, is especially poignant. In 2014, after 4-year-old Maiyanna passed away from DIPG, her mother, Mycah, donated her tumor tissue to Monje’s lab. Mycah hoped the tissue donation would drive research and someday prevent other families from experiencing unbearable loss.

Mycah also organized fundraisers in her Pittsburgh community, including a fashion show and a dance—raising more than $6,000 toward Monje’s research. This funding turned out to be pivotal. The money was used to award a summer research scholarship in 2016 to a Stanford undergraduate who screened DIPG tumor cultures in Monje’s lab. His work that summer helped the team understand that a sugar molecule, GD2, was abundantly found on the surface of most DIPG tumors. Today, this sugar molecule is being targeted by the CAR T-cell therapy used in Monje and Mackall’s clinical trial.

“Even small gifts applied at important leverage points can make a big difference,” says Monje.

In several other instances, the timing of the gifts has been especially striking. For example, Unravel Pediatric Cancer—a foundation started by another family who lost their child to DIPG—approached Monje with a significant donation just as she was exploring the next big step: testing a GD2-targeting CAR T-cell therapy in mice.

The incredible strides made by Monje’s lab would not have been possible without support that ran deep. Tissue donations from families suffering immense loss, as well as financial contributions from a wide base of donors—many of whom made gifts in memory of a child or young adult—helped launch and sustain the research at every stage.

“So many donors, foundations, and families have supported DIPG research,” says Monje. “[M]any families have even made the unthinkable gift of donating their child’s brain tumor. They have all helped to expedite our work. Every single contribution, large or small, enables us to move forward without delay and do all we can to help families fighting this terrible disease.”

An Only-at-Stanford Collaboration

The extensive show of donor support over the last decade is a testament not just to the desperate need for an effective treatment for DIPG and related cancers, but also to the trailblazing science at the heart of Monje’s research. And Stanford, it turned out, was the perfect setting for this boundary-pushing science.

Once her lab had identified a potential target in the sugar molecule GD2, Monje fostered a new relationship that would later seem fated. Mackall, a prominent investigator known for her work pioneering immune therapies for pediatric cancers, had recently come to Stanford—and she just happened to work in the same building, one hall over. In fact, Mackall had already reached out to explore the potential of using immunotherapy on childhood brain tumors. As Monje tells it, once her student discovered GD2 on the surface of tumor cultures, the path was clear. Monje simply walked over to Mackall’s office. Monje knew that Mackall’s team had already engineered a CAR T-cell therapy targeting GD2—so she asked whether they could work together to test it on DIPG and related tumors. This casual overture ended up launching what has proven to be an incredibly rich and fruitful collaboration.

In 2018, Monje and Mackall celebrated a significant milestone when they published a study in Nature Medicine showing that CAR T-cell therapy targeting GD2 could make DIPG tumors disappear in mice. The next stage of their collaboration—a human trial—was risky, due to the potential for swelling in areas like the brainstem. Monje and Mackall built in as many safeguards as possible and began the clinical trial in 2020. In 2022, they published the first promising results of this trial in Nature.

Now, in the latest findings of the ongoing clinical trial, published this week in Nature, the research shows huge potential to change the course for children and families facing DIPG and similar cancers.

A Brighter Future Ahead

Drew, the clinical trial participant who had a complete response, was diagnosed with DIPG in 2020, during his junior year of high school. As his tumor grew, he found he needed a wheelchair to get around. In June 2021, Drew received his first infusion of CAR T cells at Stanford. Though it was difficult, especially early on in the trial, he continued receiving infusions in his senior year, participating in classwork from home.

By spring 2022, Drew had improved to the point of returning to school and was able to navigate the hallways with a rolling walker. That May, he walked across the graduation stage unassisted, to a standing ovation. Now, four years after his diagnosis, Drew’s brain scans are tumor-free, and he is healthy, walking easily, and attending college. He dreams of making a career in restoring natural areas, a conservation strategy known as rewilding.

“I’m hoping they’ll learn from all my success to help other kids,” says Drew. His family is also constantly thinking of others facing the same devastating diagnosis. “There’s a lot of loss that led to this research,” says Drew’s dad. “I hope those families know that this success is because of them.”

For Monje, who first cared for a young child with DIPG 20 years ago as a medical student, and who has since devoted herself to finding effective treatments, Drew’s result only adds to her determination. The team’s analysis suggests the participants’ responses fall on a normal bell curve—meaning Drew’s complete response is not a fluke. The researchers are working hard to investigate how they can improve on the CAR T-cell therapy—as well as its application to cancers beyond DIPG—with the goal of seeing more results like Drew’s and answering the hopes of more families.

Join us on this extraordinary journey and make a contribution to support the vital research of the Monje lab.