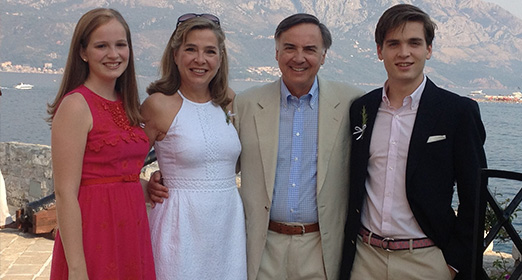

Nine years ago, David and Kori Shaw moved to Palo Alto with their 3-year-old daughter, Keegan, and 1-year-old son, Carter. Along with the usual adjustments of relocating—new job for dad, new preschool for their daughter, making new friends—there was one additional challenge to tackle.

Both Keegan and Carter had been diagnosed with severe allergies to peanut, and Carter was also allergic to milk, egg, and tree nuts. The family consulted multiple allergists in hopes of understanding their children’s allergies and keeping their kids safe.

Strict avoidance, they were told—but the danger was ever present.

With David serving as the new offensive coordinator for the Stanford Football team, Kori would arrive at the stadium with Keegan and Carter in tow and find peanuts at their feet. During one game, some spectators were throwing peanuts and the airborne dust alone was enough to trigger an allergic reaction for Carter.

This was less than a decade ago, notes Kori, yet food allergies had not yet entered the general public’s awareness and were often misunderstood as merely an annoyance—or worse, as a figment of overprotective parents’ imaginations. Families facing these deadly allergies often felt isolated.

One day at Keegan’s preschool, Kori noticed another little girl’s nametag: “Tessa,” it read, and below that, “Allergies: milk, wheat, egg, nuts, shellfish.” Kori sought out and met Tessa’s mom, Kim Yates Grosso, and the two women instantly bonded over the experiences, fears, and hopes that both their families had faced in living with dangerous food allergies.

“We were literally just trying to figure out how to live,” Kori explains, “and getting to know another family with food allergies made a world of difference. I remember walking through the grocery store, trying to find foods that were safe for my kids, and Kim on the phone talking me through it—go to aisle six and get this bread and so on—while I cried with relief.”

A few years later, Kim met Stanford immunologist Kari Nadeau, MD, PhD (see “I Can Eat It”), the first doctor she had ever encountered who was willing to try to treat Tessa’s multiple allergies. A lack of funding for food allergy research, however, was a major limiting factor in moving the work forward.

“It was evident that we needed to fundraise so Dr. Nadeau could do the trial and prove that it was possible to desensitize patients to these deadly allergies—especially kids with multiple allergies,” Kori notes.

Kim, Kori, and several other moms banded together and began rallying families—to build a community, host events, raise awareness of food allergies, and generate funding for clinical trials. Their grassroots efforts started small but grew as more and more families facing the emerging epidemic of food allergies began joining together and providing private philanthropic support for research.

Five years after the Shaws moved to Palo Alto, 8-year-old Keegan and 6-year-old Carter joined the first cohort of children to undergo Nadeau’s oral immunotherapy trial with the drug Xolair to desensitize patients to multiple allergens at the same time. Over the course of two years under the supervision of Nadeau’s team, Keegan and Carter consumed and tolerated a carefully measured, increasing dose of their allergens and were eventually desensitized to a point where accidental exposure or cross-contamination was no longer a fear.

The results were life-changing for their entire family.

“She changed our family—our whole dynamic,” Kori says. “We’re not stressed. On Sunday we took a bike ride and went downtown and had dinner in a restaurant. She gave us normal family life.”

Spreading the Word

In the meantime, word of Nadeau’s successful research had also reached another concerned set of parents—actors Nancy and Steve Carell, whose daughter, Annie, had a severe dairy allergy.

As Annie described it, having food allergies was “like living in a box.” No playdates outside their own home, no sleepovers, anxious meals at restaurants. When the family traveled, they dragged along a cooler full of food. “Every time we arrived at a hotel, it looked like we were tailgating!” Nancy recalls.

“The second I read about Kari’s success in desensitizing another child to dairy, I thought, ‘Sign us up!’” Nancy says. “Annie was 8 years old, and she hated feeling different from her classmates. I couldn’t believe that there was a possibility that she wouldn’t have to live with this the rest of her life.”

As Annie started in a clinical trial at Stanford, the Carells’ hopes were modest. “Our dream was that she could come out of an accidental exposure to dairy without serious consequences,” notes Nancy. “We weren’t thinking, ‘I hope she can eat pizza.’ We were thinking, ‘Maybe now she can hold hands with somebody who just ate pizza.’”

The experience of oral immunotherapy was not without anxiety. “We were traveling back and forth from Los Angeles, and we were basically saying to Annie, ‘Remember the food we’ve been telling you not to eat because it’s poisonous to your body? We want you to start eating it now,’” says Nancy. “I would be lying if I said it was smooth sailing from the get-go. Annie went through a lot. She has our admiration for life.”

What immediately stood out to the Carells—and what got them through—was Nadeau’s compassion and the entire research team’s support.

“We call Kari a gentle genius,” says Nancy. “During the trial [which can result in allergic reactions at home], we besieged her with phone calls. She answered every time and stayed on the phone with us until everything was under control. I trust her completely.”

When Annie successfully completed the trial, the Carells wanted other families facing food allergies to have the same opportunity. They have played an active role in supporting Nadeau’s research and in raising the public’s awareness of food allergies. In 2011, Steve volunteered to host a fundraising gala and recruited his friend and fellow actor Dana Carvey to help him raise support for food allergy research at Stanford. Steve has also narrated an hour-long documentary and participated in public service announcements to help raise awareness.

“Living with food allergies can be extremely difficult but should be approached in a positive, proactive way,” says Steve. “It’s important to support allergy research because every day they are coming closer to a permanent cure for food allergies. So there is hope.”

Advocating Early

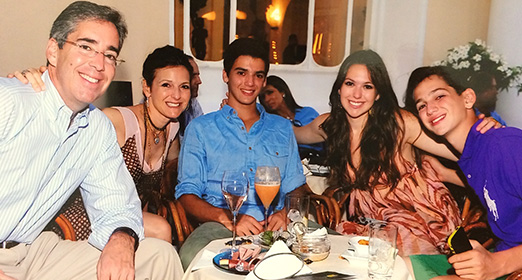

Stefan Lainovic, 22, was the first New Yorker to join one of Nadeau’s clinical trials at Stanford. When Stefan was an infant, his doctors described him as “wildly allergic” to dairy and egg. Restaurant meals and processed foods were out of the question. Any food prepared on equipment shared with egg or dairy ingredients could cause a deadly anaphylactic reaction. Like other parents of food allergic children, his mother, Rebecca, monitored everything he put in his mouth.

Stefan’s parents also took another important step: they encouraged him from a young age to advocate for himself.

“We wanted to empower him even as a little boy,” Rebecca explains, “to speak up for himself in an assertive way and be taken seriously. We knew we couldn’t always be there speaking for him. As parents, you blink and suddenly they’re off to grade school and then it’s high school, college.”

As early as age 2 or 3, any time Stefan could speak on his own behalf, he did. When the family went out to a restaurant, it was Stefan’s job to explain that he didn’t need a menu, thank you, because he had brought his own food.

Starting in preschool, Stefan carried his own EpiPen in a waist-pack along with pre-measured Benadryl. Though his family and the school staff always had backups at the ready, Stefan’s parents instilled in him that he was solely responsible, that he was in charge of his own destiny. This sense of responsibility served him well in his teenage years—a risky period when many food-allergic kids fail to carry their own medications—and saved his life on at least one occasion.

It wasn’t until Stefan was 19 years old that he finally qualified for a food allergy clinical trial. By then he was enrolled at Williams College in Massachusetts and the trial was across the country at Stanford—seemingly a deal-breaker. Thanks to what Rebecca describes as Nadeau’s resourceful and get-it-done attitude, they soon found a unique solution: it turned out Stefan could enroll in classes at Stanford while undergoing the clinical trial and earn academic credits that would transfer to Williams.

For much of the next 13 months, Stefan lived at Stanford, attending classes and working part-time in Palo Alto. Though Rebecca flew out for monthly visits, the ongoing reality of the trial was that Stefan was individually responsible for attending his “updosing” appointments (when the research team would introduce a higher dose of his allergen), ingesting his prescribed dose of milk at home each day, and keeping himself safe from possible reactions.

But in many ways, Stefan didn’t go through the experience alone.

“They say it takes a village to raise a child,” Rebecca notes, “and this is never more true than in the food allergy community.”

Everyone from Kari Nadeau to fellow parent Kim Yates Grosso to physician assistant Tina Dominguez offered support, friendship, and watchful eyes to ensure that Stefan would succeed in completing the trial.

Since then, the Lainovics have become more committed to the food allergy community than ever before. Rebecca serves on the board of directors of Food Allergy Research & Education (FARE), and she and her husband, Sacha, made strategic philanthropic gifts to sustain and further advance Nadeau’s groundbreaking work.

While Stefan has also taken part in raising awareness, he says food allergies do not define him. He now works in investment banking in New York at Centerview Partners, a demanding career that involves seven-day work weeks and eating out daily—without fear.

The Future is Bright

Today, patients from all over the country are participating in Nadeau’s clinical trials. Matthew Friend, a high school junior from Chicago, is proud to be one of them.

Matthew’s life-threatening allergies to wheat, barley, rye, and oat were discovered when he was 8 months old and broke out in full-body hives after his first taste of Gerber multigrain baby cereal. The hardest thing to avoid was wheat, which his parents soon learned was literally everywhere: in root beer, Pringles, brownies—even hand cream, shampoo, and sunblock. By the time Matthew entered high school, he had been to the emergency room at least 10 times despite his family’s vigilant efforts.

“We saw Dr. Nadeau’s work as the first glimmer of hope in 14 years for our child,” says Matthew’s mother, Linda Levinson Friend. “While other physicians were directing us to carry epi and avoid wheat, Dr. Nadeau was willing and able to set the stage for Matthew to lead a full and normal life.”

When Matthew began the trial in August 2012, just a miniscule speck of his allergen could cause anaphylaxis. Eight weeks into the trial, Nadeau instructed him to “go and get cross-contaminated” and Matthew successfully tolerated the exposure. By the end of the trial, he was eating a daily regimen of one cupcake, six Oreos, and one graham cracker containing wheat; one granola bar containing oat; and four cookies made with rye and barley flour, all of which he still continues every day in order to maintain his desensitization to the previously deadly allergens.

“We are forever indebted to Dr. Nadeau and her incredible staff,” Linda says. “They are desensitizing kids like Matthew with multiple food allergies, and exciting results are happening. It is surreal and amazing to be part of this process.”

When Matthew’s family began looking for a way to give back, they reached out to their local network in Chicago and convinced their friends and colleagues that supporting research at Stanford would actually have a national impact. Today, thanks to Linda and her husband, Bill, and the other donors they have mobilized, the clinical trials have opened sites in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles so that more families can participate in life-changing research in their own hometowns.

For Matthew, the trial made such an important difference that he began blogging for The Huffington Post about his experiences “as a human lab rat” in food allergy research, recounting his experiences and wanting other teens with potentially deadly food allergies to know there is hope for a normal life. Matthew is also quick to point out that he still carries two EpiPens—because although he is desensitized and protected from cross-contamination, the treatment is experimental and he can still have reactions.

“Whenever we are presented with an opportunity, we are happy to speak to or guide other families,” Matthew writes. “Because of the innovative and incredible work that Dr. Kari Nadeau and her team are doing at Stanford and now in other sites across the country, people with food allergies can look forward to full lives. I am living proof that the future is extremely bright for people with food allergies.”

This article first appeared in the Spring 2015 issue of the Lucile Packard Children's News.