It’s not a stretch to say that Jasan Zimmerman was born to make a difference for kids and families facing cancer. That doesn’t mean his path has been easy or straightforward. The three-time cancer survivor—first diagnosed with neuroblastoma as an infant—had many surprising stops along his personal and professional journey (including almost 12 years as a scientist!) before finding a role tailor made for him.

Today, Jasan is the senior director of Foundation Relations at the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health, where his science background, survivor’s perspective, and nonprofit expertise fuels his work to raise funds to tackle some of the hardest problems in children’s health. Recently, our friends at Cannonball Kids’ cancer Foundation (CKc) interviewed Jasan about his journey through treatment, survivorship, science and service.

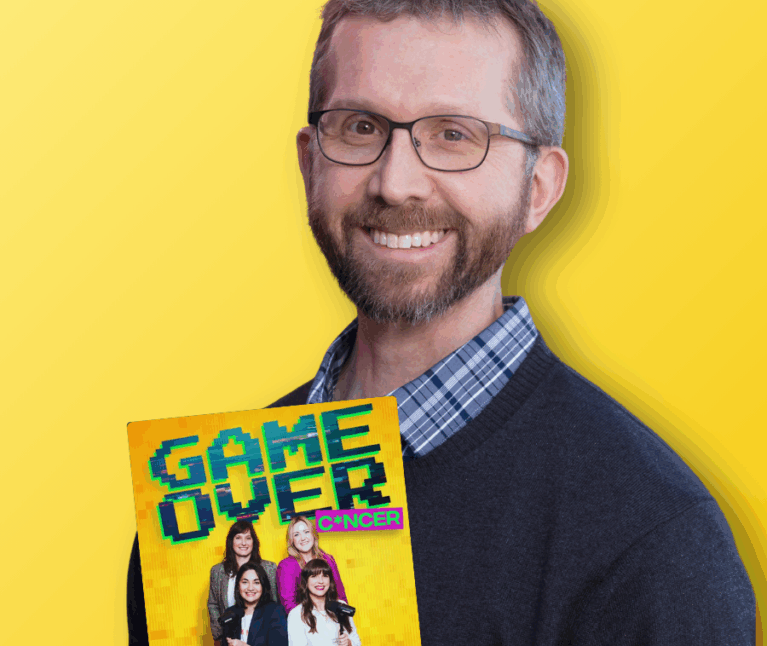

Watch the powerful vodcast—or read a few highlights—to get to know this extraordinary member of our team.

You’re a three-time cancer survivor. Can you walk us through your cancer journey?

My first diagnosis was in 1976, when I was about six or seven months old. I had neuroblastoma on the left side of my neck. The tumor was removed, and I had radiation treatment on that part of my neck. That radiation most likely caused thyroid cancer when I was 15. I had a thyroidectomy and radioactive iodine treatment. Then when I was 21, the thyroid cancer came back—I had a higher dose of radioactive iodine. My last cancer treatment was in 1997, so I’m coming up on 30 years, which is wild.

How did those experiences affect you emotionally over time? And what helped you move through it?

When I was 15, that’s when the depression hit. I didn’t want to talk about it. I buried it. From 15 through my early to mid-30s, I really struggled with mental health. There was always something missing. I still can’t even really describe it, other than feeling like I was in a bad mood.

I found a support group here in the Bay Area for adolescent and young adult cancer patients and survivors. I felt really compelled to go, but I didn’t want to go. I would get there, park, sit in the car [and] listen to the radio for 20 or 30 minutes. Eventually, I went in. I think for the first year I didn’t talk at all beyond saying, ‘I’m Jasan and here’s my cancer history.’

But there were a couple people really involved in advocacy. I credit them for sparking that idea in my brain.

How has the way you tell your story changed over the years?

At first it was, ‘Here’s my story, I’m a survivor, yay’… I just wanted to get it over with. Then it moved into: ‘Here’s what adolescent and young adult cancer survivorship looks like.’ Now… I talk about how patients should be equal partners in research. I’ve been through this for almost 50 years—I want to use that. [Cancer patients and survivors] want to tell you what we need. We don’t want to be told what we need.

You had a long career in biotech before moving into fundraising. What motivated the shift?

Like every pediatric cancer survivor, I originally wanted to be a doctor. I applied to med school a few times and didn’t get in. At the end of my senior year of college, I didn’t know what I should do, and my mom said, ‘You should go to grad school.’ I was able to enroll at Loma Linda University to study microbiology and molecular genetics. It was full circle because it’s where I was treated for the neuroblastoma [as an infant].

I was a scientist for almost 12 years. It was interesting but super tedious. [Eventually] I was laid off and that was super scary, but I had already started at the University of San Francisco in the nonprofit administration master’s program. The layoff was about halfway through that program, and I was able to transition to a Palo Alto foundation that funded basic science research. At first, I was looking into cancer advocacy, but I was doing a ton of volunteer work at the time. I had this epiphany: ‘That’s going to be a lot of cancer all the time, and that’s going to burn me out. It’s just not going to be healthy.’

Now I lead the Foundation Relations team at the Lucile Packard Foundation for Children’s Health. It lets me merge the personal, professional, and volunteer work I care about. And the cool part is that I don’t only raise money for cancer, even though it means so much to me. It gives me a balance where I’m not all cancer all the time.

What role does patient storytelling play in the research world?

Stories are incredibly powerful–that’s what drives people. The science is complicated. But when someone says, ‘All that science helped me and now I’m good,’ that hits home. We talk about this a lot on our Patient and Family Advisory Council for the Stanford Adolescent and Young Adult Cancer Program. We ask: is it the right time for this patient to become a volunteer or get involved with advocacy? Are they ready to share? Sometimes it helps process what happened. But survivors shouldn’t feel pressured to be advocates or storytellers.

What impact has Cannonball Kids’ cancer had on Stanford’s research programs?

That DIPG clinical trial from Dr. Monje—she had one patient with complete response and no tumor whatsoever. That’s a brain tumor that had basically no cure and very little progress in decades. To know that there are kids now who are going to make it because of CKc’s support—that just means a ton to me. Every donation counts, whether it’s a dollar or $100,000.

What’s something you wish more people understood about life after cancer?

Once the treatment is finished, you’re not done. Pediatric cancer is not a death sentence—but it’s definitely a life sentence. It’s a family disease—it affects everyone, not just the patient. I’d also say: ‘Get the mental health stuff dealt with—don’t bury it.’

Any closing message for survivors?

If you don’t want to climb Mount Everest or be a huge fundraiser, that’s awesome—go live your best life, whatever that looks like for you. Do whatever works best for you. Don’t feel bad about not being a ‘super survivor.’

Watch the full vodcast to learn more about Jasan—or join the community making an impact in pediatric cancer.